Eugene Country Club: A complete turnaround 50 years ago

Famed golf architect Robert Trent Jones Sr., with assistance from his son, positioned the ECC course for enduring national prominence

Fifty years ago, the fairways at Eugene Country Club echoed with the sounds of an intense, often passionate debate.

At issue was the very soul of the golf course, its legacy and its future.

The golf course that will be the site of the NCAA Division I Men’s and Women’s Golf Championships, beginning with the first round of the women’s tournament Friday and ending when the last putt is rolled in the men’s championship June 1, was born of that discussion five decades ago, and of the willingness of the membership to make a profound leap of faith.

In early 1967, amid strong dissenting opinions, the ECC membership hired noted golf architect Robert Trent Jones Sr. to redesign the course that had been created by the esteemed H. Chandler Egan in 1923, voting to accept Jones’ vision of what the golf course could be, a plan that was both inspired and possibly unprecedented.

“When he came to review the golf course, it was a cold, rainy day,” recalled longtime ECC member Bruce Chase, now 85, of that first visit by Jones in the mid-1960s. “We started out on the front side, in about four carts.

“We came in to the club at the end of the first nine to get some coffee, because it was unpleasant out there. I think Wendell (Wood, the club professional) said, ‘Well, Mr. Jones, what do you think?’

“And there had been a lot of discussion about how they were going to handle rebuilding the greens and rebuilding the traps, and what type of materials to use, and he said, ‘This is going to be a piece of cake. We just turn it around. All the water is in front of tees, it should be in front of the greens,’ or words to that effect.

“It was like somebody had hit me with a sledgehammer. It was so simple, and so obvious, and it solved so many problems. He said, ‘We won’t have to close the course down, so the members can play during construction.’ That was a real big deal.”

Jones’ revelation: He would reverse the course, putting the first tee where the 18th green had been, and the 18th green where the first tee had been.

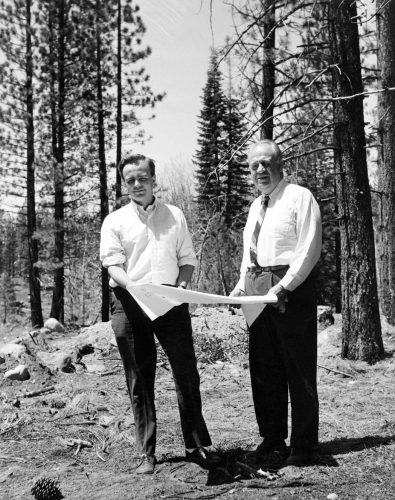

Along on that visit was Robert Trent Jones Jr., then in his mid-20s, apprenticing with his father en route to building his own storied career as a golf course architect, a career that includes Chambers Bay Golf Links, site of the 2015 U.S. Open.

“It was so stunning, it was like all the people went silent,” the younger Jones recalled earlier this month. “It was radical to do that. I believe it was the first time it was ever done in my knowledge of golf architectural history.”

For Eugene Country Club, the rest has been history, replete with U.S. Golf Association championships, several other high-profile tournaments, including the Pacific Coast Amateur, and regular appearances in the rankings of the top 100 golf courses in this country.

“It made it a premier golf course, because we’ve held several extremely important golf tournaments here, and we’ve got one coming up. Two coming up,” said longtime member Ted Larsen, now 80. “That made it all possible. We could never have done it, could never have conceived doing it, on the old golf course.”

Course at the crossroads

As recounted in “Breaking 100,” the history of the first century of Eugene Country Club written by Jeff Wallach and Todd Schwartz, the original ECC course was a nine-holer, with hole names such as “Dr. Painful” and “Nightmare,” on College Hill, west of South Willamette Street between 24th and 28th avenues, and stretching up the hill to Lawrence Street.

In the early 1920s, Wallach and Schwartz wrote, the club began looking for a site for a new golf course, with the final choices being property in the Gateway area off Harlow Road, the Lone Pine Farm area on River Road, and the present site, on what became Country Club Road, purchased for just over $54,000.

To design its new course, the club hired H. Chandler Egan, a Medford resident and a famous figure in the sport. A star at Harvard, Egan was a national collegiate champion in 1903, the U.S. Amateur Champion in 1904 and 1905, and the Olympic silver medalist in 1904. In his years as a course designer, while remaining a dominant player in Northwest amateur golf, Egan redesigned Pebble Beach and designed or redesigned courses in Oregon such as Waverly, Riverside and Oswego Lake country clubs, and Gearhart Golf Links.

Work on Egan’s ECC design began in 1923, and the first nine opened in July 1924, with the second nine opening in 1925. With its tree-lined fairways, the contours shaped by years of flooding, the course built for the hickory-shaft era remained vibrant for decades. In 1959, ECC hosted the NCAA championships, in which Robert Trent Jones Jr. competed for Yale.

Jones Jr., who missed the cut, remembers a “plainer,” narrow, “vertical” golf course, in which the tall trees — taller than the trees on the East Coast courses he regularly played — made gauging distances difficult.

By the early 1960s, even as the course was a regular stop on the LPGA circuit and Johnny Miller was winning the U.S. Junior Amateur title here in 1964, some in the club began discussing the need for a makeover. Reasons varied; when the project was finally approved, in 1967, stories in the Eugene Register-Guard cited wear on the smallish Egan greens and tee boxes — with 350 members when Egan designed the course, ECC membership had grown to 550 — and drainage issues as the compelling factors.

But, in “Breaking 100,” Wallach and Schwartz wrote that Wendell Wood, the venerable club professional, had worried quietly that the course had become too easy — there wasn’t much in the way of water hazards or fairway bunkers, although in fairness to Egan, his original design included such bunkers, perhaps eliminated for cost reasons. Wood supported a makeover, as did highly respected superintendent John Zoller. And Chase recalls that influential club members wanted “a more prestigious golf course.”

Chase said he “loved” the Egan course, and he wasn’t alone.

“There was a pretty heated dispute among the members about what should happen at that time,” he said. Some were concerned about the cost of a remodel, about losing playing time during a lengthy reconstruction and about the loss of any of ECC’s signature trees.

And then there was the fact that the course had been designed by the great H. Chandler Egan.

“A lot of people thought that was a violation of history,” Chase said. “Why should we do it over again?”

Into the future

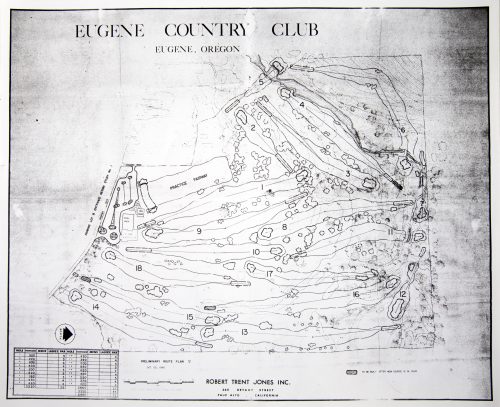

In October 1965, Robert Trent Jones Sr. created “Preliminary Route Plan C,” which is on display at Eugene Country Club and became the general blueprint for the new course. His son recalls that there would certainly have been a Plan A and a Plan B, as the design evolved. The final plan maintained the fairways of the Egan course, except in reverse, with the exception of two par 3s, No. 7 and No. 12, that Jones Sr. designed, the greens fronted by water hazards.

(Note: In the NCAA championships, the customary front nine will become the back nine, transforming the fifth-through-seventh holes into No. 14 through 16, compelling water holes for match play.)

On Feb. 1, 1967, the redesign — backed by such influential ECC members as Nat Giustina and Bob Booth — was put before the ECC membership for a vote. The following day, The Register-Guard reported that the measure, with a budget of $435,000, was approved by a vote of 194-122. Perhaps a reflection of how intense the debate had been, both Jones Sr., who died in 2000, and Jones Jr., remembered it passing “by a single vote.”

“We have no guarantee the course will be better, but we have the finest architect available,” club president Mike Marlatt told The Register-Guard then. “I think it will be the finest course in the western part of the United States.”

Construction began in the spring of 1967 and was completed in a mere six months, with members continuing to play on temporary greens and tees throughout the project. Describing himself as “the Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” Jones Jr. recalls spending much more time in Eugene than his father, who was busy with other projects — he was designing and building Mauna Kea in Hawaii and Spyglass Hill in Pebble Beach.

The shaping of bunkers and greens was done by Jones’ crew, from designs that the architect would sketch on half-sheets of paper. (The younger Jones recalls his father letting him design the green on No. 11; Jones Sr. said he would change it if necessary, but liked it, and left it.) The crew worked closely with Zoller, a key figure in the project.

Wisely, the senior Jones didn’t touch the undulating fairways, though he was tempted; a trip to Scotland, where he saw the dunes-created links courses there, apparently convinced him otherwise, and the flood-shaped terrain, with its distinctive swales, remained as it had been.

Club member Jon Anderson, a student of golf course architecture who recently reviewed Jones’ papers on file at Cornell University, where Jones Sr. had studied and where Anderson, the former distance runner, is in the hall of fame along with him, put it this way:

“The fairways were put down by God, to use that phrase. Thank God Jones didn’t take a road-grader blade to the fairways.”

By June 1967, the redesign was taking shape. A Register-Guard story reported that “Jones told ECC officials that the new No. 6,” the long dogleg par 5 to a pond-protected green, “‘could be one of my best.’”

Which is not to say that club members didn’t have ongoing concerns, but when the project was complete, those seemed to dissipate. In the view of Robert Trent Jones Jr., the Eugene Country Club course has classic elements of his father’s designs: Large elevated greens (averaging 7,500 square feet, more than twice as large as Egan’s), “face bunkers” that look the golfer in the eye and require a carry to the green, and “runway” tee boxes, dictated both by the narrow fairways and by maintenance issues — they can be mowed more efficiently.

Thirty years after the redesign, ECC hired Jones Jr. as architect-of-record, for a four-year span through 2001 in which he restored elements of his father’s original design that had been modified over the decades. Golf architects are like goalkeepers, Jones Jr. said, defending par.

“We want to create challenges that will yield,” he said, “but only to good thinking and good playing.”

At ECC, the challenges created by Robert Trent Jones Sr. endure, almost 50 years later.

“I think he took a beautiful golf course and made it more beautiful and more challenging,” Anderson said.

Said Robert Trent Jones Jr.: “It’s lasted the test of time.”

(Originally published in the Eugene Register-Guard, May 17, 2016)